republic onboarding

Internet Banking

-

Savings & Chequing

-

Savings Accounts

Growing up with a plan for tomorrow

For youths between the ages 13 to 19 years

Shape your future

Helps you to build your nest egg

Saves you time and money

The wise investment instrument

Earn more on your Foreign Accounts

Chequing Accounts

Bank FREE, easy and convenient

A world of convenience and flexibity

Invest and enjoy the best of both worlds

A value package designed for persons 60 +

Life Stage Packages

Banking on your terms

Getting married?

Tools & Guides

Make an informed decision using our calculators

Help choose the account that’s right for you

All Our Cheques Have A New Look!

-

-

Electronic Banking

-

EBS Products

Open a deposit account online

Pay bills and manage your accounts easily

Banking on the Go!

Welcome to the Cashless Experience

Top up your phone/friend’s phone or pay utility bills for FREE!

EBS Products

Make secure deposits and bill payments

Access your accounts easily and securely with the convenience of Chip and PIN technology and contactless transactions.

Access cash and manage your money

Where your change adds up

-

-

Credit cards

-

Credit Cards

Credit Cards

Additional Information

-

-

Prepaid Cards

-

Pre-paid Cards

-

-

Loans

-

overview

To take you through each stage of life, as we aim to assist you with the funds you need for the things you want to do

We make it easy to acquire financial assistance for tertiary education through the Higher Education Loan Programme

We make it easy, quick and affordable to buy the car of your dreams

Tools & Guides

Helps you determine the loan amount that you can afford

You can calculate your business’ potential borrowing repayments

Republic Bank's Group Life Insurance will provide relief to your family by repaying your outstanding mortgage, retail or credit card balance in the event of death or disablement.

-

-

Mortgages

-

Mortgage Centre

Republic Bank Limited can make your dream of a new home a quick and affordable reality

New Customers

Block for MM- new user mortgage process

There are three stages you must complete before owning your first home

Tools & Guides

block for MM - personal - mortgages

-

-

Investments

-

Investment Products

-

All Eyes on Central Banks

You are here

Home / All Eyes on Central Banks

To combat the widespread economic dislocations caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, most countries rolled out extraordinary fiscal and monetary policy measures, starting as early as February 2020. Regarding the monetary policy, many central banks reduced their policy rates to record low levels and where practicable, adopted aggressive asset purchasing programmes (bond purchases). This extremely accommodative policy stance, was directed toward preserving some level of commercial activity by boosting systemic liquidity in the financial sector and reducing the cost of borrowing thereby, facilitating greater lending. For most countries, the extremely accommodative stance, along with elevated government expenditure, averted what would otherwise have been a much deeper plunge in economic activity. In fact, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its April 2021 issue of the “World Economic Outlook”, estimated that the 3.3 percent global contraction that occurred in 2020, could have been three time as large, were it not for the various fiscal and monetary interventions. Even so, the economic losses arising from measures to control the virus are quite substantial, prompting assurances from major central banks that their easy money policies will remain in place until output returns to 2019 levels or at least their respective economies are imbued with sufficient stability.

Now that the expansion of vaccination programmes is facilitating the gradual re-opening of many economies, the outlook for global economic activity, particularly for developed countries, has improved. Nevertheless, a lot of the COVID-19-related supply chain disruptions that were first manifested in 2020, remain in play and as such, represent a major impediment to commercial activity. These interruptions have resulted in significant bottlenecks in the aggregation, manufacture, transport and distribution of several goods, ranging from raw materials to final products. As it relates to the transportation and distribution of goods, higher shipping costs, partly influenced by increased fuel prices and logistical challenges at some ports (due to unexpected labour shortages) are among the major hindrances. Apart from ports, labour shortages have hampered the recovery of other sectors, including restaurants, with virus-related fears and the cushion of government transfers, delaying the return of some workers in certain jurisdictions. Altogether, these supply chain challenges have been stoking inflationary pressures since the first quarter of 2021, forcing central banks to seriously consider the prospect of beginning to unwind their easy monetary policy much earlier than initially envisaged and well before the full recovery of their respective economies. This note briefly examines the responses of a few major central banks to the rising price pressures they have been facing in recent months.

The US

In the US, the Fed Funds rate (the benchmark interest rate) remains at 0-0.25 percent, after being cut in March 2020 and the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) bond buy-back programme continues, as it seeks to safeguard the country’s economic recovery. Notwithstanding the Fed’s accommodative stance, yields in the US were trending up in the first four months of 2021. The increase in yields were driven in part by the expectation among some investors, that the Fed would begin to increase the benchmark rate and thereby reverse its policy stance, sooner that initially envisaged. Beside rising inflation due to labour and supply shortages, this view was based on the faster-than-expected recovery of real GDP and encouraging employment figures, facilitated in part by the country’s fiscal injections and ongoing vaccination campaign. However, in April 2021, Fed Chairman, Jerome Powell, moved to assuage those fears, indicating that there were still significant risks to the economy, particularly with unemployment still above desirable levels. A major objective of the Fed is for a recovery of the labour market to 2019 levels, when unemployment was 3.5 percent. Accordingly, the Fed was of the view that the economy still needed further support, with unemployment at 6 percent in March 2021.

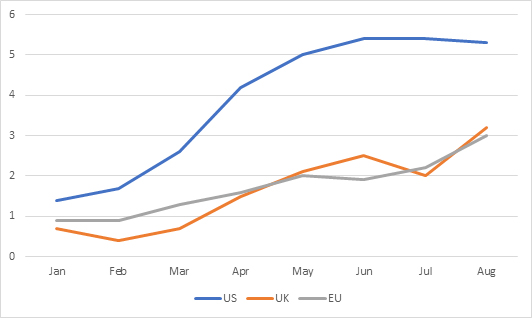

Since rising 60 basis points above the Fed’s target rate (2 percent) in March 2021, the inflation rate has surged further to reach 5.3 percent in August (Figure 1). Against this backdrop, some market observers were expecting the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to announce plans to pare its bond purchasing programme in its September monetary statement. However, no such announcement was made, which is a clear signal that the Fed believes the economy is not yet on solid enough footing for such a move. After all, at 5.2 percent in August, unemployment remained well above pre-pandemic levels. Additionally, with much of the inflationary pressures emanating from dislocations caused by the pandemic, they are expected to gradually ease as more of the global and domestic economies re-open. Also weighing on the Feds decision would have been the uncertainty related to the Delta variant, the failure of Congress to agree to increase government’s debt ceiling by the time of the FOMC meeting and the potential for a government shutdown. The decision was also influenced by global risks, including the potential collapse of highly indebted Chinese real estate conglomerate Evergrande, which some experts warn could have a similar impact to the failure of Lehman Bothers Holdings Inc. 13 years ago. Nevertheless, with rising prices eroding consumer purchasing power, the Fed is also facing growing calls from certain segments of the business and political communities to pull back some portion of its current policy. Given these opposing pressures, the accommodative monetary stance is expected persist through 2022, with the Fed likely to slow asset purchases before cutting its benchmark rates, whenever it decides to begin to roll back its pandemic response measures. In this regard, no increase in the policy rate is expected before the second half of 2022, at the earliest.

The Eurozone

The European Central Bank (ECB) had adopted an accommodative policy stance long before the emergence of the pandemic, to stimulate the economy and to raise inflation to its 2 percent target rate. After a further reduction in September 2019, the ECB’s policy rates remain in the -0.5 percent to 0.25 percent range. The €20 billion per month Asset Purchase Programme (APP) was also restarted in November 2019. However, to mitigate the economic strains associated with COVID-19, the ECB instituted a temporary asset purchasing programme called the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), with a total envelope of €1,850 billion. Bond yields rose in the first quarter of 2021, a period in which the ECB’s bond purchases under the PEPP had fallen, though purchases under the APP continued. The period was also defined by spikes in COVID-19 infections, with new rounds of lockdown measures in several countries. Acknowledging the risks posed by these two developments, the ECB revealed its intention to significantly increase its bond purchases in the second quarter. This statement calmed fears that tighter monetary conditions were emerging and as such resulted in a fall in bond yields in the Euro zone.

In its September monetary policy announcement, the ECB underscored its continued commitment to conduct net asset purchases under the PEPP until the end of the crisis phase of the pandemic or at least until the end of first quarter 2022. Unlike the Fed however, the ECB indicated that based on the outlook for inflation and current financing conditions, it intended to reduce the rate of purchases at this time. The Bank is confident it can maintain favourable financing conditions at a moderately lower pace of bond purchases but stands ready to make the necessary adjustments when needed. In August, inflation surged to 3 percent, which represents a 10-year high for the EU and came in the wake of a greater-than-expected 2 percent GDP expansion in the second quarter. Even so, the Bank left its policy rates unchanged, communicating its expectation for the rates to remain at current or lower levels until it judges that inflation will stabilise at the 2 percent target over the medium-term. This demonstrates the ECB’s willingness to endure periods where inflation rises temporarily above the target. While this latest policy statement calmed fears that the Bank would shift to a hawkish policy stance (where low inflation is the top priority) too soon, it induced anxiety among some stakeholders, particularly those fearful that the high inflation rate may become persistent. Nonetheless, the ECB is likely to maintain its policy rates at current levels through 2022, although it may decide to further slow the pace of its asset purchases over the next six months. As in other jurisdictions, it goes without saying, that the Bank’s policy decisions will be influenced by the developments related to COVID-19 and the Fed’s policy actions.

Figure 1: Inflation Rate (%)

The UK

In its March 2021 policy announcement, a full year after it cut its base rate to an historic low, the Bank of England (BOE) communicated its decision to leave the rate unchanged at 0.1 percent. However, just one month prior, with the economy under tremendous pressure, the BOE warned that lenders should be prepared for negative interest by July 2021, in the event such a policy became necessary. However, there proved to be no need for this measure, as growing vaccination programmes and the consequent easing of lockdown measures, facilitated an uptick in economic activity in the ensuing months. Nonetheless, with the economy still facing severe challenges the BOE was expected at that time to maintain its accommodative policy stance including its quantitative easing programme (asset purchases) for quite some time.

With dislocations caused by COVID-19 and some BREXIT-related factors triggering further increases in inflation during the third quarter of 2021, the BOE has also found its policy announcements subject to substantial speculation and anxiety. In August, inflation rose by 3.2 percent, notably above its target rate (2 percent) with core inflation reaching its highest level since 2011 at 3.1 percent. Prices are projected to increase by 4 percent in the fourth quarter of 2021 and could register above 4 percent in the first half of 2022, given surging gas prices. However, the Bank is mindful of signs of the slowdown in economic activity during the third quarter, with real GDP in July only 0.1 percent above the levels of the previous month. In fact, based on current performance, economic activity is still 2.1 percent below the UK’s pre-pandemic levels. Additionally, the BOE took the opportunity to point out that in its view, inflation is expected to return to the target rate over the medium-term, with the elevated pressures currently being experienced likely to prove transitory. Consequently, after review, the BOE deemed its current monetary stance to be appropriate given the needs of the economy at this time, and therefore it decided to maintain its policy rate at 0.1 percent and preserve its asset purchases. Some observers expect that surging inflation will force the Bank to begin to tighten its policy by mid-2022. If this assessment turns out to be true, these efforts are expected to begin with a reduction in the asset buying programme.

Trinidad and Tobago Since it reduced its benchmark rate the “Repo” from 5 percent to 3.5 percent in March 2020 and reduced the reserve requirement for commercial banks from 17 percent to 14 percent, the Central Bank has not altered any of the tools of its monetary policy. However, given the pandemic-imposed depression of both the energy and non-energy sectors, the demand for credit continues to be unspectacular. In this environment, high levels of liquidity continue to characterise the domestic financial sector, more than a year after these major adjustments by the Central Bank. Excess system liquidity expanded to average $9.5 billion in 2020, from $4 billion in 2019, before falling moderately to $8.6 billion in the first seven months of 2021.

The domestic economy is expected to register 1 percent contraction in 2021, before an improved performance in 2022. However, real GDP is not expected to return to 2019 levels before 2023 at the earliest. Given its desire to stimulate economic activity, the Central Bank is not expected to increase rates for the foreseeable future. This view is supported by the fact that inflation remains at manageable levels (2.2 percent in July 2021) notwithstanding notable increases, particularly in the food component in recent months. All the same, it should be noted that Central Bank policy, more specifically that of its Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), could be complicated by narrowing TT-US short-term interest rate differentials. Increases in US yields caused the differential for three-month Treasuries to fall from 86 basis points in August into negative territory (-1 basis point) in December 2020, before rising to 26 basis points in July 2021. If the spread falls into negative territory, local investors will seek more attractive investments abroad at an increasing rate. This will increase both capital flight and foreign exchange pressures and thereby make the setting of monetary policy more complex. This is because the MPC would be forced to choose between stimulating economic growth or limiting capital flight at a time when both objectives are critical. In this regard, changes in US yields is expected to significantly influence Central Bank’s monetary policy.

Conclusion

Given the critical mandate of Central Banks to facilitate stable economic growth and control inflation, it is natural that their policy decisions are attracting the great level of attention they are now. Confronted, as they are by a confluence of tremendous uncertainty surrounding the COVID-19 virus, the need to protect nascent recoveries in the wake of an historic global recession and the need to promote stable prices, their roles could hardly be more complicated. For now, it seems like global Central Banks are prepared to prioritise stimulating growth, with there still being substantial downside risks. The Banks are confident in their belief that the current inflationary pressures will ultimately prove to be transient. This assessment is hinged on the continued removal of economic restrictions globally, which will eventually address the shortages and bottlenecks that are now hindering commercial activity. Accordingly, the success of COVID-19 vaccination programmes will be pivotal, in particular their effectiveness regarding increasing vaccine equity among nations and reducing hesitance within the population.

COMPANY INFORMATION

Banking Segments

Press & Media

Contact Us

© 2026 Republic Bank Limited. All Rights reserved.

Garvin Joefield

Garvin Joefield